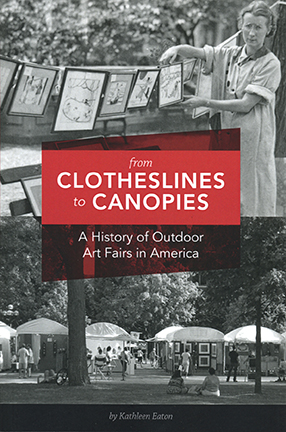

Creative Conversations with Kathleen Eaton, Chicago-based painter and author of the recently-published book From Clotheslines to Canopies, A History of Outdoor Art Fairs in America.

Kathleen Eaton has been selling her oil paintings at galleries and art fairs for many years and has experienced the business since the time before canopies came into use. Eaton tells us about her new book, and the process that went into documenting the fascinating and little-known history of outdoor art fairs.

Hello Kathleen, and thank you for discussing your new book with us! What inspired you to take on the task of writing this book?

I have exhibited at art fairs for many years, and over this period of time have had countless discussions with other artists about the business. During those discussions, it was often expressed that art fairs and their history would be a great topic for a book. I don’t consider myself a writer but, I thought it would be important to begin assembling this history since soon many of the people that had experienced the early years would be gone. Of course, those who participated in the really early years are long gone. In my years before art fairs, I worked in libraries so collecting the information was something I was comfortable with.

What was your research process like? How did you find your sources?

Throughout the book, I tried not to rely on any one source for information to be sure dates, places and names were as accurate as possible. I felt that finding photographs of early fairs was going to be essential to this book, so that was my primary priority. Since I had participated in the Plaza Art Fair and they feature their history, I knew that the story of American outdoor art fairs would probably begin in the early 1930s. Thus, this project began with a hunt for the 1932 photograph of the Plaza show.

East Coast Shows

After looking into the Plaza photograph, I pursued information on the Rittenhouse Square Fine Art Shows and the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit, as I heard from other artists that these were very old shows. I scheduled a visit with John Morehouse, the Washington Square executive director, and he was invaluable in providing information about the show. Incidentally, the Salmagundi Club, where our meeting was held, is one of the oldest arts organizations in the United States, dating back to 1871. It has quite an archive on art in addition to the records of the Washington Square show. While not super well-known among artists in other parts of the country, Washington Square had an enormous influence in New York in the years between 1931 and 1950. Morehouse mentioned the Smithsonian Archives of American Art had a collection of clippings about the show that had been saved by its founder, Vernon C. Porter. I was able to use this archive to study those records of the show from 1930 to 1940. By the way, the American Art Archives in Washington DC has probably the cheeriest, most helpful staff I’ve ever encountered in a government agency!

My search of early East Coast shows also led me to the Nantucket Sidewalk Art Show, that started in 1930. The Artists Association of Nantucket and the Nantucket Historical Society were very helpful and generous with early newspaper clippings and photographs. For the Rittenhouse Square show, I was only able to find sketchy records. For better records, I would probably have needed time to dig through historical records in Philadelphia — something I just wasn’t able to do for this book. It seemed like the city had a vibrant arts community that did informal street exhibits in the early 20th century, but I could not find concrete examples.

The History of 12 Shows Turns into the History of 13 Shows

I had settled on 12 shows beyond the first four East Coast shows I had researched until I received my regular ZAPP e-blast and noticed that the Bellevue Arts Museum Artsfair was 66 years old! I looked into the show and found out they started as a spin-off from the arts museum. This is totally unique in the annals of art fairs, which is why it was included.

Further Research

To obtain information about the non-East Coast shows featured in the book, I contacted show staff, researched online, and contacted historical societies and local libraries. Many of the details were obtained from phone interviews with past and present show directors.

The Bellevue Arts Museum ArtsFair, the 57th Street Art Fair, the Old Town Art Fair, the Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival and the Lakefront Festival of Art have all had books published by their committees, and I was gratefully able to obtain these books to use as references. The Ann Arbor shows have a great archive publicly available on the Ann Arbor District Library website, but the best information was obtained from previous Street Art Fair directors Susan Froelich and Shary Brown.

The University of Miami has an extensive source of photographs in its archive on the Coconut Grove Arts Festival. I had hoped to find a connection to former CGAF show director Terry Stone Ketover, who was instrumental in its development, but was unable to do so. Some of the dead ends like this were frustrating because I know there is much more interesting information that could have been included in this book.

Inclusion of Craft Shows

I did also include the Northeast Craft Council Shows, although the history of craft fairs is more of an indoor phenomena. In early years, shows were a combination of outdoor and indoor events. Because of that, I felt that craft shows should be captured in this history. I know a craft artist, David Bacharach, that was an early participant in craft shows. I wrote him and expected a few anecdotes but ended up with a whole chapter of information! I did double check all his information in the records of the American Craft Council as well as relying on other sources.

The Final Picture

The final picture that I wanted to include was the painting by Thomas Hart Benton of the Washington Square exhibit. After extensive trips to the Ryerson Library at the Art Institute in Chicago, I ended up finding it on Google Images (and felt really stupid for not trying that first!) On a happy note, while looking at the Art Institute collection, I typed in ‘art fair’ in their search engine and found the woodblock print by Branislaw Bak of the Old Town Art Fair.

What was your favorite image included in your book?

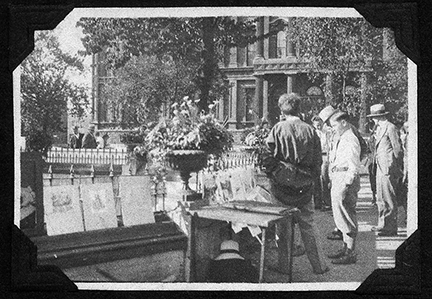

My favorite photograph of an early show was given to me by Barbara Hughes, an artist from Wisconsin. This is the one of the Cathedral Square show in Milwaukee that her father founded in 1932. Although the show only lasted a few years, it likely influenced others in that area to continue the tradition of outdoor exhibiting.

What did you uncover in the history of art fairs that really surprised you, and would likely surprise others as well?

I soon realized that fairs in this country developed as a reaction to economics — specifically the depression of the 1930s when most everyone was scrambling to survive. Artists were especially hard hit, and it drove them to find different ways to market their work. This has some parallels to the recent financial collapse. It drove some artists to look for new ways to sell their work at art fairs, and of course, it drove some out of the business because they could no longer financially survive.

“One of the frequent claims I saw about the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit was that Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were early exhibitors.”

I was very surprised at how esteemed the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit was during its early years and that all the major New York museums supported the show. Support from museums is mostly absent at current art fairs, except for the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Bellevue Arts Museum.

One of the frequent claims I saw about the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit was that Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were early exhibitors. They did not appear in any of the art fair programs of the 1930s, so I can only conclude that they were never officially exhibitors. The only reference to this claim that I found was in a biography of Jackson Pollock. It mentioned that in 1932 during the show, he took some of his work down to the front stairs of his home and tried to sell it. Apparently, nothing sold and that was the extent of his involvement. One of the show’s regular portrait artists, Joseph Delaney, did draw a picture of him that day, could be proof that Pollock was there.

Why do you think it’s important, perhaps especially for present day art fair artists, to know about the history and progression of art fairs?

The history is really interesting. Art fairs are, in truth, part of the American art arena and the artists who participate in them are part of a unique “art movement.”

Based on your findings regarding the past and present trends in the art fair world, do you have any predictions for the future of the industry?

I was very tempted to include a chapter on this subject but decided it was wiser to leave predictions out of the book because in 10 years they would probably be laughable. Right now I believe there are loosely two categories of people that attend art fairs: those that come just to be entertained by looking at the work and those that are (at least potential) buyers. Because of the economy, buyers for expensive work are in short supply. I don’t know if this younger generation values art highly enough to purchase it. I don’t think younger people are as acquisitive as the older generation in terms of actual handmade art, but that is a topic open for much discussion.

“Right now I believe there are loosely two categories of people that attend art fairs: those that come just to be entertained by looking at the work and those that are (at least potential) buyers.”

In terms of artists, I believe there will always be people who are driven to create original objects — whether fine art or craft. These same people will also likely be attempting to sell their work in order to afford this continue creating. Art fairs seem to be a vehicle that serves this need.

As to the fairs, the ones that focus on the art and artists seem to have the most enduring success, in my experience as an exhibitor. Yet, there are a few exceptional shows that had a great focus on the art but died because of poor management. As art fairs are driven mostly by the market economy, the country’s economic state is a heavy dictator of success or failure. Another factor that can be hugely influential to the future of art fairs is the Internet and the way information is disseminated. It can be difficult to speculate how things will turn out. However, I do believe the industry will withstand any challenges.

From Clotheslines to Canopies, A History of Outdoor Art Fairs in America is available for purchase on Amazon. Also, go to artfairhistory.com for more information about the history of art fairs.