This is part of a series of posts highlighting the art fair and festival industry. Know someone we should talk to? Email your suggestions!

Creative Conversations: An interview with digital artist Michael Brown

Michael Brown is a Chicago based artist who specializes in lenticular printmaking and 3-dimensional imagery. He has been exhibiting at art shows for 7 years now. You can find more information about him and see his work at michaelbrown.com

Over the summer, ZAPP intern Anna Charney spoke with Brown about his unusual process and history as an an artist.

ZAPP: What did you do before you began to do art fairs and what brought you into this field? For how long have you been a working artist?

Brown: Prior to my career as a fine artist, I worked for Kodak. I’ve been involved with art most of my life, but I transitioned to full time in 2006 and have supported my family with art since then.

My first art fair was actually in the early 70’s. My older sister was a jeweler and was going to exhibit at an outdoor show in Milwaukee. She encouraged me to join her and show some of my photography. At that time I was just out of high school. I sold nothing at that show, but enjoyed the experience of having people look at my work and thought that someday I would like to be a full time artist.

In 1995, I found the “200 Best” art shows issue of Sunshine Artist on a magazine rack at a bookstore. The idea of exhibiting entered my mind once again, but was still dormant for a few more years since I was fully occupied with a demanding career and a young family. In 1998, I was talking to a friend and neighbor and the topic of art shows came up. We were both curious if shows could be a venue to show and sell some of our photography. Our first show was a tiny local show in the town where we lived. They let the two of us display together in a single booth spot. We split the booth fee ($35 was my share) an E-Z UP and five Graphic Display panels. I sold about $400 of small photographic prints at that weekend show and was thrilled.

After that, my neighbor and I each started exhibiting separately, although he no longer does outdoor art shows. Each summer for the next few years I would exhibit at various Midwest shows on a part time basis. It was a family affair, with my wife and two young daughters joining me. I enjoyed participating at art shows and meeting the public. I went full time in 2006. From 1998 to 2007, I was exhibiting traditional large format color photography, primarily landscapes. After 2007, I was exhibiting my kinetic and 3D optical art.

ZAPP: What is your educational background in the arts, if you have one?

Brown: My interest in art dates back to the 4th grade. I happened to live in an amazing and well-funded public school district. My grade school had both full time art and music teachers. I can remember doing woodworking, image transfers, painting, ceramics, and even stained glass. One of my stained glass pieces hung in the school’s library for many years. In high school I started art classes, but the teachers expected my paintings to be as good as one of my older sisters and they were not. I still remember my frustration of a value study where we had to paint a grid of colored squares of different hues. The instructor would then photograph the painting with black and white film, and the result was supposed to look like a plain gray rectangle since all the hues were to have the same value. That assignment made me realize that my sisters would always be the better painters and that I was going to concentrate exclusively on photography. I had been reading Popular Photography magazines and was frustrated that I couldn’t start photo classes at school until sophomore year. My high school had an amazing darkroom and I took three years of classes in photography and was part of the yearbook staff. In my senior year, my parents suggested that art photography probably wasn’t as good a career choice as something more practical.

It actually was a college Physics class that changed the direction of my life. Once day in the lecture hall, the professor showed a film that contained various high-speed motion picture clips that showed things too fast for the eye to see in very slow motion. I was fascinated by the idea of scientific applications for photography. As I continued coursework in geology, astronomy, and meteorology, I noticed that I enjoyed using the instrumentation of science more than the science itself. I particularly liked anything to do with scientific imaging, such as weather satellite images, or the stereoscopes used to view aerial photos. I decided to switch schools and later obtained a degree in Photo-Electronics. My coursework involved designing and building electronic trigger systems, short duration electronic flash units, and learning to use all sorts of film cameras including 4×5 view cameras and 10,000 frame per second motion picture cameras.

During that time, I learned the dye transfer printing process and how to develop both still and motion picture film. After obtaining that degree, I later returned to school as a working adult to get a second degree in Business Management. My first career was selling high-speed electronic imaging systems to various corporate and government accounts. These systems sold for between $35,000 and $150,000. During this time, I was recruited by the Eastman Kodak Company and spent 18 years there in various technical and management positions.

As a photo enthusiast, I purchased my first copy of Photoshop (version 1.7 in 1991) after reading about it in a magazine at the grocery store. I thought digital photography would be the way of the future and I wanted to learn all about it. I told my wife that I wanted to buy a computer to learn image processing and we had to take out a loan to purchase a color Macintosh, which was so primitive by today’s standards.

I wrote a small book on how to get started with image processing that I sold mail order by taking out classified ads in photography magazines. My knowledge of digital imaging paid off when Kodak decided to open four electronic imaging centers around the country. After they read my self-published book, I was transferred to Dallas in 1993 to open the imaging center there. My years at Kodak gave me very early exposure to many of the digital tools and techniques used by photographers today. I was using Kodak digital SLR cameras way back in 1993, when they retailed for $30,000, long before Nikon or Canon knew how to build them. This background gave me the technical foundation and understanding that allowed me to develop my optical art process years later.

ZAPP: How did you originally come up with your unusual process of making optical art?

Brown: My optical art process is known as lenticular printmaking. It is based on a few optical principles that are over 100 years old. I remember seeing some simple examples of it as a child. In the early 1980s, I purchased a 4-lens 35mm camera called the Nimslo that was designed to make 3D lenticular prints that you could view without using a stereoscope or glasses. It didn’t work very well and the company went out of business a few years later, but the whole thing intrigued me.

During my time at Kodak, I was involved in a couple of experiences where I saw examples of the technology, so it was something I was aware of, but the cost and complexity of the process made it unsuitable for making single prints. As time progressed, advances in digital imaging made it technically possible for me to experiment with making lenticular prints in my home studio. I started by trying to make 3D pictures, and quite frankly most of my experiments were failures. It took me over two years before I started getting promising results. The lenticular process is not well documented and there are very few people working in this medium. Over the past few years I have invented some new techniques that have allowed me to really advance the field. Some of my newest pieces appear both 3D and animated. I have one picture in my booth that is a self-portrait, and people often look behind the panel to see if there is a real person in the frame.

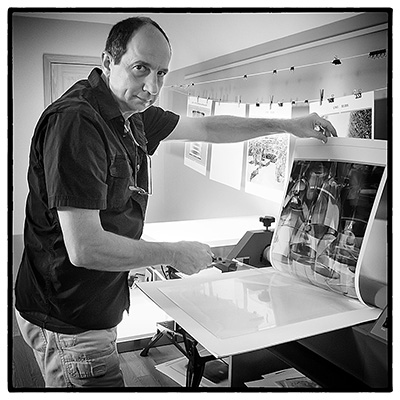

Michael working in his studio.

ZAPP: What inspires you to make each piece and what determines your subject matter?

Brown: I’m inspired by the wonder and beauty of life. I find the way almost everything works to be complex and miraculous. I primarily work on art and concepts that interest me personally. My hope is that if I like something, the public that attends the art shows I’m at will like it too. Most of my pieces deal with transformation and many of them are nature themed. During the past year, I’ve been exploring the idea of incorporating more motion or animation in my art, and those pictures tend to be figurative. My biggest challenge is the jury process since neither the 3-D nature of my art or the animated qualities can be seen in the still images that art shows use for jury.

ZAPP: What is your studio and sketching process like?

Brown: My studio is an oversized room over my garage. It’s well equipped and has room for me to experiment as well as create my art. My process begins by creating an image sequence. This can be a set of still photographs or even frames extracted from a video. The images are divided into very fine stripes, interlaced, and printed on a sheet of white film. After drying the film, I transfer it to a ribbed lenticular screen, bonding the two pieces together with an optically clear adhesive. The art is then matted and framed for wall display.

ZAPP: What has been your favorite or most encouraging experience at an art show?

Brown: My favorite art show experience is when the judges select me for an award. My art is very non-traditional, and the process is not taught in schools, so most judges have no real understanding of the process, so an award is rare and special to me.

My most encouraging experience is when the public comes out and purchases my art. Without the public’s financial support, I couldn’t continue living this wonderful lifestyle.

ZAPP: What made you choose to do that art shows over galleries and museums?

Brown: I do exhibit my art in galleries and museums, but generally these venues offer very limited sales opportunities. The attendance at art shows is much higher than the typical gallery or museum show. Gallery and museum shows are nice for one’s C.V. or resume.

ZAPP: How do you plan out your schedule every year?

Brown: Over the summer I start making a spreadsheet of potential shows for the following year. I need to do around 20 shows per year, and I like to spread them out over a ten month period. About half of my shows will be local (Chicago area). I will travel to Florida and Texas during the months when it is too cold in the north to do outdoor shows. Since my 3D and animated art does not show up well in the still photo jury process, I apply to about 50 shows. I often double apply for certain weekends. I use personal experience, other artist’s recommendations, and lists like Sunshine Artists or Art Fair Source Book to create my list of potential shows. Almost all of shows I do are listed on ZAPP. There are only a few that are listed on the other jury systems.

ZAPP: As an artist who has been exhibiting in fairs and festivals for several years, what are some trends and shifts that you have witnessed in this business?

Brown: There are fewer full time artists than when I first started. The majority of artists I see are now over 50. Electronic applications have replaced slides and postage. Jury and booth fees are higher. The Sprinter has become a favorite art fair van. Smart phones, the Internet, and social media have all had a big impact. The phones are now mobile credit card terminals, weather radar, GPS for navigation, and cameras for taking show shots. The Internet has made researching shows easier, been an additional sales vehicle for some, and is an inexpensive way for artists to have an online presence for their patrons. Facebook groups are now a primary source of good art show information and have greatly reduced the value of older online forums. There are many more ways and places for people to purchase art. The gallery business model is no longer as prominent as many galleries have closed.

ZAPP: What do you see for the future of fairs and festivals? Where do you hope they are headed and what do you see as threats to the industry?

Brown: The top twenty or thirty fine art shows will continue to be great events in their communities, attract amazing artists, and provide strong selling environments. Those shows will remain highly competitive.

There has already been a decline in the next tier of shows. Those shows are struggling to attract enough good artists. The quality of art at those shows is diminishing, which lowers the public’s interest in attending. There is still hope for those shows to remain relevant to their communities, and good venues for artists. These are the shows that should be attending the trade conferences to learn about “best practices” and network with other show directors. The tier of shows lower than that are no longer art shows, but places to buy imported goods, sunglasses, doggie treats, and plants. Many of these shows will disappear.

The biggest threats to this industry are changing demographics, changes in public interests, and the employment prospects for today’s youth. My observation is that both artists and attendees are older adults. There are fewer people that have a desire or the means to own original art.

People are not as amazed by traditional art as they are by new technology. If I think back thirty years ago, almost any artist at an art fair would have amazed me. A hand crafted ceramic vessel or a painting would be pretty rare and valued items in those days. Where else would you find such art? Today, art is mass produced, and available 24/7 online or at mass merchandisers. Also many people today are part of the do-it-yourself movement and want to create their own art. Finally, the economy has changed. We currently are in a slump where people are having a hard time finding good paying jobs, are often in debt, and many are worried about not saving enough.

What gives me confidence is that, as self-employed artists, we can use our creative aptitudes and adapt our business model to the times. There are still millions of people in the United States with excess money who can afford art. I also feel that artists by their nature continue to create and innovate and that new work keeps the art fairs fresh and interesting.

I expect that digital technology will have a greater presence in art shows as artists use the tools of their age, and waves of college art graduates have been educated in the possibilities. Photographers were among the first art show artists to explore digital technology. Now, it is rare to find a photographer that still uses film. Artists can now draw and paint with a computer. There are all sorts of alternative printmaking techniques and image transfer processes that use digital printing in some way. Some jewelers and sculptors will use 3-D design software. Who knows what impact 3-D printing will have? I think these evolving technologies will keep the art shows fresh and exciting for the next generation.

ZAPP: If you could have given one piece of advice to yourself five years ago, what would it be?

Brown: Really think through the various opportunities that present themselves. Understand and be willing to say no to activities that take a lot of time but produce little revenue. There are too many distractions that can take time away from creating new artwork.

ZAPP: Any advice or thoughts that you would like to share to emerging artists who are just joining the industry?

Brown: Decide if you are doing this as a hobby or business and run it as such. If it’s a hobby, pick shows in areas you want to vacation in. Enjoy eating out, and savor the experience. If it’s a business, keep good records, make your decisions based on data, and control your costs. Statistically, half your shows will be below (the mean) average so don’t get discouraged. Enjoy the journey and make friends with your booth neighbors. The shows are easier and more fun if you have a companion and helper (in my case, my wife). I read a quote once that I find appropriate: It takes twenty years to become an overnight success. Keep that in mind as you make your first five-year plan.

–By Anna Charney

Anna Charney studies studio painting and drawing at The School of The Art Institute of Chicago. She is a Denver native and decided to spend her 2013 summer back at home hanging around the ZAPP offices as an intern to learn about the arts festival business. While they share a last name and an excellent fashion sense, she is not related to ZAPP’s managing director, Leah Charney. You can see her artist’s gallery at www.annacharneyart.com.